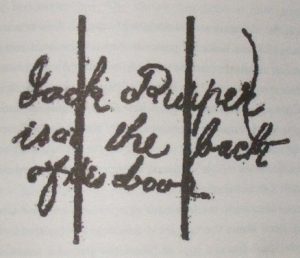

The Princes Street graffiti (“Jack Ripper is in this seller” and “Jack Ri(p)per is at the back of this door”) were chalked at the rear of William Bury’s residence in Dundee. The identity of the person or persons who wrote the graffiti is unknown. The two messages are apparently in two different hands (e.g., compare the appearance of the capital letters in the two messages), and there has been speculation, both in 1889 and in recent years, that the messages were chalked by local children, although it isn’t clear why local children would have chalked them, as, according to the February 12, 1889 Dundee Advertiser, the messages “were older than the discovery of the tragedy” (Ellen Bury’s murder). The Goulston Street Graffito was also written in chalk, and this has led to speculation that William Bury could have chalked the messages at the back of his residence. William Beadle, on the other hand, in his book Jack the Ripper Unmasked, proposed Ellen Bury as the author of the messages (1).

We are fortunate to have reproductions of the graffiti, which were published in the February 12 Dundee Advertiser. The key to resolving the mystery of the authorship of the graffiti lies in the handwriting of the two messages. If, from a handwriting standpoint, we can determine that the messages were written by two different people, then it is reasonable to conclude that the messages must have been written by local children. If, on the other hand, we can determine that the messages were written by the same person, then this points toward either William or Ellen Bury being the author of the messages. A schoolboy would have had no reason to chalk the messages in two different hands, but either William or Ellen Bury could have done this as a means of deflecting suspicion away from themselves.

The main reasons to believe that the messages were chalked by two different people are that the capital letters are formed differently in the two messages, there is a very irregular baseline in the “seller” message but not in the “door” message, the first two lines of the “seller” message display a sloppiness or lack of skill not found in the “door” message, and with respect to the word, “this,” which occurs in both messages, there is significant lateral spacing between the “h” and the “i” in the “seller” message, but not in the “door” message.

Since the messages have the appearance of being written in two different hands, if either William or Ellen Bury wrote them, then at least one of the messages, and so presumably both messages, must have been written in disguise. In 2014, Kate Alison Lafone completed a doctoral dissertation at the University of Birmingham, An Examination of the Characteristics of Disguised and Traced Handwriting (2), and this dissertation can serve as a fairly recent literature review on the topic of disguised handwriting. Lafone writes, “very often graffiti will be created in a disguised hand” (3), so we should certainly be open to the possibility that the messages were written by one of the Burys. Let’s look at some of the characteristics of disguised handwriting to see if we can find evidence of these characteristics in the two messages, and let’s also see if we can find evidence that the messages were written by the same person.

While Lafone did not observe this pattern in her own study, she notes that “an examination of the empirical studies shows that an alteration of a text’s capital letters will occur more commonly than an alteration to its lower-case letters” in disguised handwriting (4), and “the disguise technique that was found to be most common across all educational groups was the alteration of the formation of capital letters” (5). With respect to the lower-case letters, Lafone notes a study which “maintains that any such modifications will typically be made to only the first and/or last letter of a word” (6). The capital letters are formed differently in the two messages of the Princes Street graffiti, but the lower-case letters appear generally very similar. Where we observe clear variation (compare the “i” in “is” in the “door” message with the “i” in “in” in the “seller” message, and the “t” in “the” in the “door” message with the “t” in “this” in the “seller” message), we are seeing it in cases involving the first letters of words. Hence, according to some empirical studies, the general pattern of letter formation in the two messages is consistent with the messages being disguised handwriting by a single person.

One sign of disguised handwriting is inconsistency in how individual letters are formed within the same text (7). In the “door” message we see on one occasion a “t” with a crossing bar present (“at”), while on another occasion we see a “t” without one (“the”). The i-dot is missing from the “i” in the word “Ripper” in the “seller” message, but present in all three other instances of the letter within this text (given the presence of an obscuring vertical line, it is difficult to determine if the i-dot is missing from the word “Ri(p)per” in the “door” message). In samples of disguised handwriting, alterations are often made to the initial or terminal strokes of a letter (8). In the “seller” message, the “i” in “is” begins with a very small but noticeable initial stroke, while in the word “in,” the initial stroke of this letter is absent. In the “door” message, the “t” in “this” begins with an initial stroke, while the “t” in “the” lacks one. The terminal stroke of the letter “r” exhibits variation within each message as well; it can either stay flat or level with the baseline, or it can curl upward. The identical pattern in the two messages (one flat and one upward curling terminal stroke in each message) is consistent with the two messages being written by the same person.

What’s also of interest is the size of the letter “t” in the two messages. Lower-case letters occupy one or more of three writing zones. Small lower-case letters like “c” or “e” occupy only the middle zone. Others, like “p” and “g,” occupy both the middle zone and the lower zone, the lower zone being the zone beneath the baseline. Still others, like the “h” or the “t,” occupy both the middle zone and the upper zone. In both messages of the Princes Street graffiti, the “t” is noticeably shorter than other tall letters like “b,” “d,” “h” and “k” (like the “t,” the “l” also appears shorter, but unfortunately there is no “l” in the “door” message for comparison), either staying within the middle zone or extending upward just a bit into the upper zone. The shortness of the letter “t” in the two messages is another sign that the messages were written by the same person.

In the first two lines of the “seller” message, the writing appears to be sloppier or less skillful than it does in the two succeeding lines. Lafone cites studies which indicate that “to adopt a skill in writing that is less than the writer actually possesses is, in fact, one of the ‘most common’ methods of disguise” (9). In connection with the lack of skill seen in the first two lines, the baseline of the second line is very irregular. Lafone notes, “Extreme variations in the baseline of a signature or extended text will produce an abnormally erratic appearance which should immediately render the writing suspicious and probably disguised” (10). Lafone also cites a study which showed “where erratic writing precedes even, rhythmic writing…disguise is likely to be the underlying cause” (11). The “seller” message is a classic example of this, the first two lines exhibiting less skill than the two that follow them.

Inconsistency in lateral spacing is a characteristic that is rare in disguised handwriting (12). In both messages of the Princes Street graffiti, however, the terminal “r” in “Ripper” is written close to the preceding letter, while in the final word of both messages, the terminal “r” is swept well over to the right of the preceding letter. This shared characteristic is consistent with the two messages being written by the same person. In addition, in the final word of each message, the middle zone letter “r” is written noticeably larger than the preceding letter, which is also a middle zone letter. This is another sign that the two messages have a common author.

In summary, then, there are signs that the Princes Street graffiti are specimens of disguised handwriting, and there are signs that they were chalked by the same person. The handwriting characteristics which suggested that the messages could have two different authors (different formation of capital letters, a lack of skill and an irregular baseline in one message but not the other, and inconsistency in lateral spacing) could also be in accord with disguised handwriting by a single person. If the messages were indeed written by either William or Ellen Bury, who is more likely to have been the author?

Unfortunately, there are no examples of chalked messages by either William or Ellen Bury that we can use for comparison to the graffiti, and so we must look elsewhere to try to make a determination. At William Bury’s trial, Ellen’s sister Margaret Corney testified that Ellen “wrote ill, and never when she could help it” (13). In contrast, Corney testified that William Bury could write in “several hands” (14), which indicates that Bury was experienced in disguising his handwriting, and indeed there are two extant samples of Bury’s disguised handwriting, the letter that he wrote to Corney on Ellen’s behalf, in which he pretended to be Ellen, and the Ogilvie forgery that he used to persuade Ellen to move with him to Dundee. William Bury, then, possessed the writing skill necessary to create messages in two different disguised hands, while Ellen Bury does not seem to have possessed that skill.

Further, Ellen Bury would seem to have had no reason to chalk the two messages at the back of the Princes Street residence. If she had wanted to inform the world that her husband was Jack the Ripper, she could simply have walked into a police station in Dundee and reported him, as Bury often went to pubs by himself when he was in Dundee, and he would not have known that she had left the residence. William Bury, however, could have had a possible motive for chalking the messages. He had a corpse in the back room of his residence following Ellen’s murder, and if he had become concerned about local children snooping around the back of the residence and possibly breaking into the residence while he was off drinking at a pub (Bury was not in his residence at all times following Ellen’s murder), Bury could have chalked these messages to scare them away. According to the February 12 Dundee Courier and Argus, a neighbor claimed that “there were some wild boys prowling about” (15) on the evening the police were investigating Bury’s residence. It’s certainly possible, then, that there were some wild boys prowling about the back of the residence in the days following Ellen’s murder, and the behavior of these boys could have angered and alarmed Bury. By chalking these messages, Bury would have been letting these boys know, in no uncertain terms, who he really was, but inasmuch as the messages were made to appear as though they had been chalked by local children, Bury would plausibly have been able to deny ever having written them. William Bury is the obvious candidate for being the author of the Princes Street graffiti.

References

(1) Beadle, William. Jack the Ripper Unmasked. London: John Blake (2009): 272-4.

(2) Lafone, Kate Alison. An Examination of the Characteristics of Disguised and Traced Handwriting. PhD thesis. Birmingham: Univ. of Birmingham (2014). https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/5201/2/Lafone-Ward14PhD.pdf

(3) Ibid., 38.

(4) Ibid., 46.

(5) Ibid., 47.

(6) Ibid., 48.

(7) Ibid., 81, 85.

(8) Ibid., 87-8.

(9) Ibid. 59.

(10) Ibid., 244.

(11) Ibid. 91.

(12) Ibid., 64.

(13) Trial Transcript from the Trial of William Henry Bury for the Crime of Murder. JC36/3. National Archives of Scotland. 1889.

(14) Ibid.

(15). “Shocking Tragedy in Dundee.” Dundee Courier and Argus (12 Feb. 1889): 3.